Undernutrition and the prevalence of anemia in the Philippines continues to be a significant health problem, despite National Nutrition Surveys showing a steady decline in the past ten years.

According to the latest 8th National Nutrition Survey, conducted in 2013, those who suffer most from anemia are children; with 39.4 % of Filipino infants aged 6 months to 1 year suffering from the disease (compared to 66.2% in 2003).

It’s not surprising the highest rates of malnutrition - underweight, stunting and wasting - are recorded in rural areas, says Tabogon Rural Health Clinic’s municipal nutrition action officer, Dr Oliver Alino.

In remote barangays (communities) like Tabogon, “malnutrition is rampant,” he says, citing social and economic factors, such as food insecurity and diet inadequacies as key contributors to the area's health status.

“Right now the Nutrition Council of the Philippines ranked Tabogon the 30th municipality that is under nourished.

“These are the children that lag behind, out of the 60 plus municipalities in Region 7, says Alino.

Alino’s concern for the children in his municipality is echoed in the latest Nutrition Survey, which paints a critical picture of malnutrition among infants and young children living in rural areas.

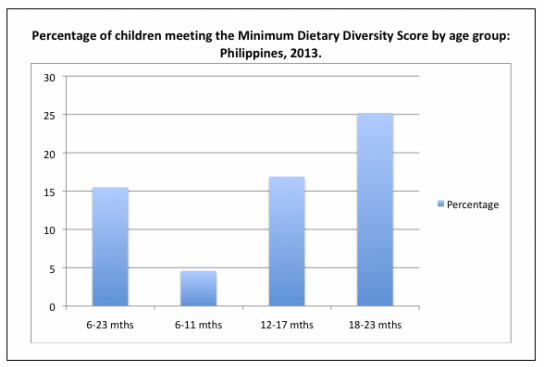

“Compared to the previous Survey, the percentage of children under 2 years of age, who met the minimum dietary requirements decreased [from 21.6% in 2011] to 15.5% [in 2013],” says Nutrition Center of the Philippines (NCP) executive director Dr Ina Castro.

According to the latest 8th National Nutrition Survey, conducted in 2013, those who suffer most from anemia are children; with 39.4 % of Filipino infants aged 6 months to 1 year suffering from the disease (compared to 66.2% in 2003).

It’s not surprising the highest rates of malnutrition - underweight, stunting and wasting - are recorded in rural areas, says Tabogon Rural Health Clinic’s municipal nutrition action officer, Dr Oliver Alino.

In remote barangays (communities) like Tabogon, “malnutrition is rampant,” he says, citing social and economic factors, such as food insecurity and diet inadequacies as key contributors to the area's health status.

“Right now the Nutrition Council of the Philippines ranked Tabogon the 30th municipality that is under nourished.

“These are the children that lag behind, out of the 60 plus municipalities in Region 7, says Alino.

Alino’s concern for the children in his municipality is echoed in the latest Nutrition Survey, which paints a critical picture of malnutrition among infants and young children living in rural areas.

“Compared to the previous Survey, the percentage of children under 2 years of age, who met the minimum dietary requirements decreased [from 21.6% in 2011] to 15.5% [in 2013],” says Nutrition Center of the Philippines (NCP) executive director Dr Ina Castro.

The infants most at risk of micronutrient deficiencies are those aged 6 to 11 months, explains Castro.

“Only 4.6% of them were able to meet the minimum diet diversity score.

“These are the infants who are weaning and are usually given only porridge; meat or fish is only added occasionally and vegetables are rarely added to the infant’s diet,” she says.

The diet diversity among infants in rural settings was also worse than their urban counterparts, in four out of the Surveys five socio-economic groups.

“[It is] what we call ‘hidden hunger,’ explains NCP nutritionist Beia Mendoza.

“It’s called ‘hidden hunger’ because at first we may not feel it, like normal hunger. It is more on the quality of food that people eat.

“People can be not hungry literally, but if the quality of their food is not that good they can experience ‘hidden hunger’ by not getting enough vitamins and minerals from the food that they have."

This kind of malnutrition is also prevalent in our country, she says.

“Only 4.6% of them were able to meet the minimum diet diversity score.

“These are the infants who are weaning and are usually given only porridge; meat or fish is only added occasionally and vegetables are rarely added to the infant’s diet,” she says.

The diet diversity among infants in rural settings was also worse than their urban counterparts, in four out of the Surveys five socio-economic groups.

“[It is] what we call ‘hidden hunger,’ explains NCP nutritionist Beia Mendoza.

“It’s called ‘hidden hunger’ because at first we may not feel it, like normal hunger. It is more on the quality of food that people eat.

“People can be not hungry literally, but if the quality of their food is not that good they can experience ‘hidden hunger’ by not getting enough vitamins and minerals from the food that they have."

This kind of malnutrition is also prevalent in our country, she says.

Earlier this year, Mendoza and her colleagues conducted a series of nutrition education sessions on the use of micronutrient powders (MNP) to reduce vitamin deficiencies like anemia, in 40 of the countries most disadvantaged communities.

The communities were selected based on the municipality’s number of GIDA barangays (Geographically Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas), says Mendoza.

“Based on our conversations with the health workers and the mothers living there in the GIDA barangays we learnt that the food that they give to their children, sometimes it’s just rice, rice porridge, or sometimes rice with dried fish.

“It’s actually difficult for a lot of them to go to the market since some of them are living in mountainous areas and they can go down to buy food only once a week, and they do not have refrigerators so they cannot store their food."

Primarily MNPs are used to address micronutrient deficiencies such as iron deficiency anemia, vitamin a deficiency, and iodine deficiency disorder in emergency settings.

“One of the reasons we wanted to visit these barangays was to introduce them to MNP, so that [municipalities] could consider using it in their nutrition programs,” she says.

ALSO READ: Peer-to-peer education: Reducing malnutrition in the Philippines

Mendoza points to World Health Organization’s recommendation in using MNPs for infants and children aged 6 to 23 months, where the rate of anemia in children under five years of age is 20% or higher.

In the Philippines, its almost 40%, she says.

“In other countries they have seen success stories in the use of micronutrient powder, such as in Indonesia.

“MNPs were distributed to [200,000] infants affected by the [2004 Indian Ocean] tsunami and earthquake and there was less prevalence of anemia among MNP recipients than non-MNP recipients.

“They can be very useful in increasing the micronutrient content of the food of the infants, especially for those living in isolated areas…and areas of conflict," she says.

“It’s not the answer for all the malnutrition problems in the Philippines,” says Dr Alino, but “it plays a great part in increasing the nutrition of the children in our municipality.”

“Of course, we continue to promote that parents should give their children good food, a balanced and diverse diet, on top of giving micronutrient powders to their children,” says Mendoza.

Music: Arche 7, courtesy of Patrick Allen Browning from the Dwelling of Objects

The communities were selected based on the municipality’s number of GIDA barangays (Geographically Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas), says Mendoza.

“Based on our conversations with the health workers and the mothers living there in the GIDA barangays we learnt that the food that they give to their children, sometimes it’s just rice, rice porridge, or sometimes rice with dried fish.

“It’s actually difficult for a lot of them to go to the market since some of them are living in mountainous areas and they can go down to buy food only once a week, and they do not have refrigerators so they cannot store their food."

Primarily MNPs are used to address micronutrient deficiencies such as iron deficiency anemia, vitamin a deficiency, and iodine deficiency disorder in emergency settings.

“One of the reasons we wanted to visit these barangays was to introduce them to MNP, so that [municipalities] could consider using it in their nutrition programs,” she says.

ALSO READ: Peer-to-peer education: Reducing malnutrition in the Philippines

Mendoza points to World Health Organization’s recommendation in using MNPs for infants and children aged 6 to 23 months, where the rate of anemia in children under five years of age is 20% or higher.

In the Philippines, its almost 40%, she says.

“In other countries they have seen success stories in the use of micronutrient powder, such as in Indonesia.

“MNPs were distributed to [200,000] infants affected by the [2004 Indian Ocean] tsunami and earthquake and there was less prevalence of anemia among MNP recipients than non-MNP recipients.

“They can be very useful in increasing the micronutrient content of the food of the infants, especially for those living in isolated areas…and areas of conflict," she says.

“It’s not the answer for all the malnutrition problems in the Philippines,” says Dr Alino, but “it plays a great part in increasing the nutrition of the children in our municipality.”

“Of course, we continue to promote that parents should give their children good food, a balanced and diverse diet, on top of giving micronutrient powders to their children,” says Mendoza.

Music: Arche 7, courtesy of Patrick Allen Browning from the Dwelling of Objects

RSS Feed

RSS Feed